Medical Condition Description

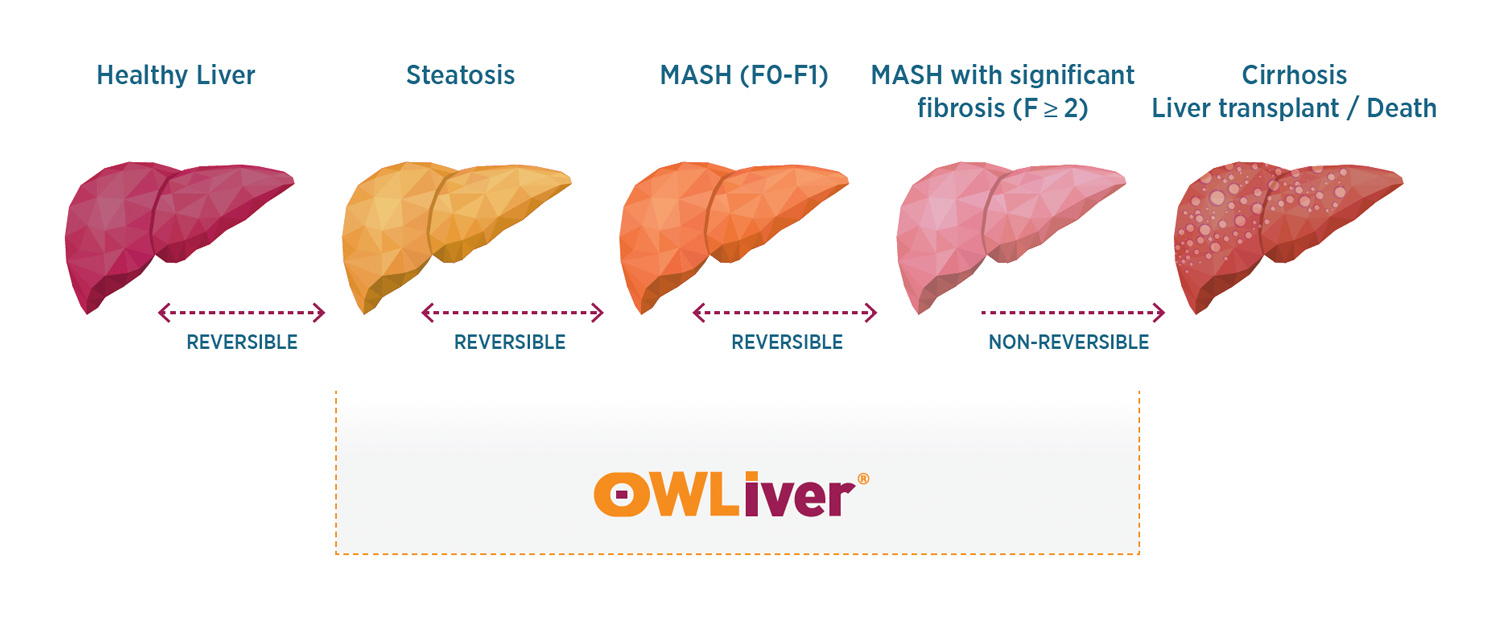

The OWLiver® test makes it possible to establish the degree of development of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD)1, previously known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Liver damage secondary to metabolic disorders represents an increasing pathology worldwide. Considering its progressive nature, from metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver (MASL) towards metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH), fibrosis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, early diagnosis, therapeutic interventions, risk stratification for disease progression, and patient monitoring are of paramount importance for an optimal standard of care. MASLD begins with the accumulation of triglycerides in the liver (steatosis), which in some individuals generates an inflammatory response (steatohepatitis) that can progress to fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver cancer (Figure 1).

Data from epidemiologic studies2 show that approximately 20% of MASLD patients develop MASH and of those, 20% progress to advanced fibrosis. It is expected that by 2030, MASH cases will increase by 29% against the backdrop of the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes (T2D) in the United States. MASLD affects about 70% of people with T2D, which highlights the importance of early screening and implementation of prevention measures to control disease progression. A high prevalence of liver fibrosis has been reported in patients with T2D, and epidemiological studies have indicated their increased risk of developing end-stage liver disease and hepatocarcinoma. In addition, the coexistence of MASLD and diabetes elevates the risk of chronic complications, such as cardiovascular disorders, chronic kidney disease, retinopathy, and both sensorimotor and autonomic neuropathy. The spectrum of MASLD includes isolated steatosis that may progress to MASH, fibrosis, and eventually cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.

Patients with significant fibrosis (stage 2 or higher, ≥F2) and advanced fibrosis (stage 3 or higher, ≥F3) have been shown to have a higher risk of morbidity and mortality3,4. Thus, clinical trials, especially phase 3 registry trials, have focused on MASH with ≥F2, also known as “at-risk MASH.”5

Altered lipid metabolism is also associated with MASLD progression; alterations in liver and serum lipidomic signatures are good indicators of disease development and progression5. Proactively identifying patients with a higher risk of disease progression, preventing unfavorable outcomes, and providing superior management that can reduce the mortality for all cases should be of top priority.

Burden of Illness

MASLD is the leading cause of chronic liver disease, affecting 25% of the general population worldwide and is the leading cause of cirrhosis and liver transplantation in women.2-6 In the United States, MASLD affects an estimated 30%-40% of adults. In patients with MASLD but without advanced fibrosis, cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of mortality. 15-20% of patients with MASH develop liver disease that ends in DEATH due to liver failure.

The economic burden of MASLD, especially left untreated, is staggering, with related healthcare costs in the U.S. estimated to be in the billions annually.3

- These costs encompass direct medical expenses related to liver disease management and indirect costs from loss of productivity, disability, and premature mortality.

- As the prevalence of obesity and T2DM continues to rise globally, the incidence of MASH is expected to increase, leading to higher economic costs.

- In the US, MASH is the fastest-growing cause of liver transplants overall, and in females, the leading cause.

- The economic impact of MASH is a critical concern for healthcare systems, policymakers, and patients, underscoring the need for effective prevention, early detection, and management strategies to mitigate its financial burden.

Current Care Limitations

Several professional organizations [American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE), and American Diabetes Association ADA)] provide recommendations on a clinical care pathway for risk stratification and management of patients with MASLD, highlighting the need for routine screening for at-risk populations (T2D, obesity, metabolic syndrome) with emphasis on non-invasive tests (NITs) such as the FIB-4 score. The AGA7, AASLD8 and AACE9 recommend an initial risk assessment by primary care physicians and endocrinologists using a NIT, FIB-4, as a first step. If value is <1.3, it is highly unlikely that the patient is at risk. However, if a score is >1.3, further testing and risk stratifications is required. AASLD guidelines also recommend the use of NITs with high negative predictive value (NPV) to exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with a clinically suspected or established MASLD.

In the most recent update by AGA Expert Review10 to provide clinicians with guidance on the use of NITs the authors emphasize the importance of integrating NITs into clinical practice for early detection of liver disease to optimize patient outcomes and minimize invasive procedures. The guidance offered is that when FIB-4 is over 1.3 sequential testing should be performed with additional NITs (e.g., enhanced liver fibrosis [ELF] test, vibration-controlled transient elastography [VCTE, FibroScan], or magnetic resonance elastography [MRE]). The AGA Update also mentions that although FibroScan is a valuable tool, its accuracy depends on proper use, patient factors, and adherence to quality measures, with at least 10 validated measurements, thus sequential testing with other NITs is recommended for optimal clinical management.

Limitations of Current Clinically Available NITs for Sequential Testing After Initial FIB-4 > 1.3

Currently, there are NITs available that are recommended by AGA and AASLD for patients with FIB-4 >1.3 but come with substantive limitations (see Table 1 in Appendix). The ELF test (Enhanced Liver Fibrosis) is a blood test that measures three specific markers of liver fibrosis; although it is useful in identifying patients at risk of progressing to cirrhosis. ELF was not specifically developed for MASLD. In addition, it can be influenced by conditions unrelated to liver fibrosis, such as systemic inflammation, kidney disease, or other systemic diseases, which leads to suboptimal performance, and the interpretation of ELF scores can be affected by demographic factors, potentially leading to misclassification. The FibroScanR (FS) is an imaging medical device that uses ultrasounds to measure liver stiffness and assess liver fat. It is not broadly available in most PCP and endocrinologist offices, and it requires specific training of personnel for correct use and interpretation of images. In addition, evidence has shown that the accuracy of FibroScan in patients with severe obesity (BMI over 40 Kg/m2) is significantly reduced.11 Other imaging medical devices like MRE (Magnetic Resonance Elastography) and MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) are costly and not available in primary care offices.

Diagnostics Breakthrough

While there have been advances in NITs for MASLD, one important current consideration, as described above, is their limited usefulness in detecting early stages of MASLD. They are designed to capture patients well into later stages of disease, which is reflected by considerable fibrosis. There has been a lack of robust and well-validated blood tests for the noninvasive assessment of early disease before it is so advanced that expensive imaging, medications, or invasive procedures will be required. Early diagnosis of MASLD can lead to delayed progression or even reverse the disease.12 Similarly, over-diagnosing mild MASLD can lead to overtreatment and associated harms, unnecessary medications and invasive procedures, with their associated financial cost to payers and distress to patients.

OWLiver® was devised to fill the above clinical gap, i.e., the need to detect disease prior to progression to significant fibrosis. OWLiver® is a blood-based test easy to implement in clinical practice that was specifically designed to address the above-described limitations presented by other non-invasive assessment methods, and to be used when a patient presents with risk for MASH, such as a FIB-4 score of 1.3 or higher or significant risk factors such as obesity and abnormal liver function tests.

The OWLiver® test is easy, fast, reliable, and non-invasive, and identifies not only severe disease but also provides insight regarding critical stages of MASLD where intervention is needed the most. After a FIB-4 of 1.3 or higher the OWLiver® test allows for the assessment of MASLD at any stage of the disease, thus mediating early interventions to avoid progression, optimize patient outcomes, minimize invasive procedures and ultimately reduce healthcare costs. OWLiver® contributes to the optimization of current multi-test assessments by reducing the present heterogeneity and subjectivity of interpretation.

Due to the test design, OWLiver® is the only blood test that can assess all stages of MASLD, from early steatosis (liver fat) to steatosis with inflammation to significant and advanced fibrosis.

References

- Barr J, Caballería J, Martínez-Arranz I, Domínguez-Díez A, Alonso C, Muntané J, et al. Obesity-dependent metabolic signatures associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease progression. J Proteome Res. 2012;11(4):2521 -32.2.

- Barr J, Vázquez-Chantada M, Alonso C, Pérez-Cormenzana M, Mayo R, Galán A, et al. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry-based parallel metabolic profiling of human and mouse model serum reveals putative biomarkers associated. J Proteome Res. 2010;9(9):4501 -12.

- Mayo R, Crespo J, Martínez‐Arranz I, Banales JM, Arias M, Mincholé I, et al. Metabolomic‐based noninvasive serum test to diagnose nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: Results from discovery and validation cohorts. Hepatol Commun. 2018;2(7):807 -20.

- Bril F, Millán L, Kalavalapalli S, McPhaul MJ, Caulfield MP, Martinez-Arranz I, et al. Use of a metabolomic approach to non-invasively diagnose non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(7):1702 -9.

- Martínez‐Arranz I, Mayo R, Banales J, Mincholé I, Ortiz P, Bril F, et al. Non‐invasive serum lipidomic approach to discriminate non‐alcoholic steatohepatitis in multiethnic patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatol. 2019; 70(1):1030A.

- Noureddin M, Mayo R, Martínez-Arranz I, Mincholé I, Cusi K, Bril F, et al. Serum-based Metabolomics Advanced Steatohepatitis Fibrosis Score (MASEF) for the non- invasive identification of patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis with significant fibrosis. J Hepatol. 2020; 73(1): S136.

- Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202-209

8. Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions,risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):11–20.